|

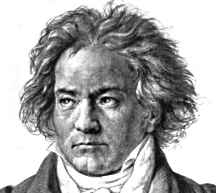

Beethoven,

Ludwig van (1770-1827), German composer, considered one of the greatest

musicians of all time. Having begun his career as an outstanding improviser

at the piano and composer of piano music, Beethoven went on to compose

string quartets and other kinds of chamber music, songs, two masses,

an opera, and nine symphonies. His Symphony No. 9 in D minor op. 125

(Choral, completed 1824), perhaps the most famous work of classical

music in existence, culminates in a choral finale based on the poem

"Ode to Joy" by German writer Friedrich von Schiller. Like his opera

Fidelio, op. 72 (1805; revised 1806, 1814) and many other works, the

Ninth Symphony depicts an initial struggle with adversity and concludes

with an uplifting vision of freedom and social harmony. II. Life Print

section Beethoven was born in Bonn. His father's harsh discipline

and alcoholism made his childhood and adolescence difficult. At the

age of 18, after his mother's death, Beethoven placed himself at the

head of the family, taking responsibility for his two younger brothers,

both of whom followed him when he later moved to Vienna, Austria.

In Bonn, Beethoven's most important composition teacher was German

composer Christian Gottlob Neefe, with whom he studied during the

1780s. Neefe used the music of German composer Johann Sebastian Bach

as a cornerstone of instruction, and he later encouraged his student

to study with Austrian composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, whom Beethoven

met briefly in Vienna in 1787. In 1792 Beethoven made another journey

to Vienna to study with Austrian composer Joseph Haydn, and he stayed

there the rest of his life. The combination of forceful, dramatic

power with dreamy introspection in Beethoven's music made a strong

impression in Viennese aristocratic circles and helped win him generous

patrons. Yet just as his success seemed assured, he was confronted

with the loss of that sense on which he so depended, his hearing.

Beethoven expressed his despair over his increasing hearing loss in

his moving "Heiligenstadt Testament," a document written to his brothers

in 1802. This impairment gradually put an end to his performing career.

However, Beethoven's compositional achievements did not suffer from

his hearing loss but instead gained in richness and power over the

years. His artistic growth was reflected in a series of masterpieces,

including the Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major op. 55 (the Eroica, completed

1804), Fidelio, and the Symphony No. 5 in C minor op. 67 (1808). These

works embody his second period, which is called his heroic style.

Around 1810 Beethoven was especially drawn to the poetry and drama

of German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, whom he met in 1812 through

the initiative of Goethe's young literary friend Bettina Brentano.

Bettina's sister-in-law Antonia Brentano was probably the intended

recipient of Beethoven's famous letter to the "Immortal Beloved."

The letter dates from July 1812 and apparently marks the collapse

of Beethoven's hopes to seek happiness through marriage. Following

this disappointment, Beethoven's output declined significantly, and

during 1813 he was generally depressed and unproductive. Beethoven's

fame during his lifetime reached its peak in 1814. The enthusiastic

response of the public to his music at this time was focused on showy

works, such as Wellington's Victory op. 91 (1813; also known as the

Battle Symphony), and a series of patriotic crowd-pleasers, including

the cantata The Glorious Moment op. 136 (1814), but his enhanced popularity

also made possible the successful revival of Fidelio. During the last

decade of his life Beethoven had almost completely lost his hearing,

and he was increasingly socially isolated. He had assumed the guardianship

of his nephew Karl after a lengthy legal struggle, and despite Beethoven's

affection for Karl, there was enormous friction between the two. Notwithstanding

these difficulties, between 1818 and 1826 Beethoven embarked upon

a series of ambitious large-scale compositions, including the Sonata

in B-flat major op. 106 (Hammerklavier, 1818), the Missa Solemnis

in D major op. 123 (1823), the Thirty-Three Variations on a Waltz

by Diabelli in C major op. 120 (1823), the Symphony No. 9 in D minor

op. 125 (1824), and his last string quartets. Plagued at times by

serious illness, Beethoven nevertheless maintained his sense of humor

and often amused himself with jokes and puns. He continued to work

at a high level of creativity until he contracted pneumonia in December

1826. He died in Vienna in March 1827. III. Music Print section Beethoven's

music is generally divided into three main creative periods. The first,

or early, period extends to about 1802, when the composer made reference

to a "new manner" or "new way" in connection with his art. The second,

or middle, period extends to about 1812, after the completion of his

Seventh and Eighth symphonies. The third, or late, period emerged

gradually; Beethoven composed its pivotal work, the Hammerklavier

Sonata, in 1818. Beethoven's late style is especially innovative,

and his last five quartets, written between 1824 and 1826, can be

regarded as marking the onset of a fourth creative period. Although

Beethoven's music of the early period is sometimes described as imitative

of Mozart and Haydn, much of it is startlingly original, especially

the works for piano. His early piano sonatas often have a forceful,

bold quality, which is set into relief by the searching inwardness

of the slow movements. The Sonata in C minor op. 13 (Path�tique, 1798),

the most famous of these sonatas, transfers Haydn's practice of employing

slow introductions to his symphonies to the genre of the sonata. The

title refers to a quality of pathos or suffering, which is felt especially

in the brooding slow introduction and is twice recalled in later stages

of the first movement. The main body of this swift, brilliant movement

seems to convey willful resistance to the sense of suffering that

dominates the slow introduction. At the threshold of his middle period

Beethoven sought a variety of new approaches to musical form. In the

Sonata in C-sharp minor (Moonlight, 1801), he begins with a slow movement,

while typical sonatas of that time began with a fast movement. The

movement's placid motif (repeated phrase) of broken chords is reinterpreted

in the final movement as forceful figuration reaching across the entire

keyboard. The sonatas of op. 31, from 1802, each open in an original

fashion. The G major, op. 31 no. 1, begins with striking shifts in

key, in contrast to the usual practice of remaining in the same key

to "ground" the listener. The D minor, op. 31 no. 2 (Tempest), on

the other hand, breaks up the opening theme into contrasting segments

in different tempi, whereas customary practice called for stating

the theme in its entirety at the beginning of a movement. In the first

movement of the Eroica Symphony, one of the major works from Beethoven's

middle period, he again sought ways to expand upon the prevailing

musical forms. At that time, composers usually organized movements

in three major parts. First, the exposition introduces the musical

themes of the piece. Next, the development takes these themes into

other keys, often modifying or fragmenting them. Finally, the recapitulation

restates the themes, grounded in the original key. Prefaced by two

massive, emphatic chords, the opening theme of the Eroica lingers

on a mysterious dark moment of harmony�a gesture that is not reinterpreted

until much later, at the outset of the recapitulation. After the rhythmic

climax of the enormous development section�it is twice as long as

the development section in any other symphony of the time�Beethoven

reshapes classical norms by introducing extensive new material, which

is resolved in a sort of recapitulation in the coda (concluding passage),

which follows the movement's recapitulation. The four movements of

the Eroica bear the following expressive associations: struggle, death

(a funeral march), rebirth (a scherzo, or rapid dancelike movement,

that begins quietly), and glorification. In its narrative design,

the Eroica is connected to the ballet music of Beethoven's Prometheus,

op. 43 (1801), from which he borrowed the theme for the symphony's

finale. This movement of the symphony expresses the exaltation of

the Greek mythological figure Prometheus in a series of variations

on the ballet's theme. Beethoven had originally intended to dedicate

the work to French general Napoleon Bonaparte, whom he idolized, but

he angrily withdrew the dedication after learning that Napoleon had

taken the title of emperor. Beethoven's other instrumental works from

the period of the Eroica also tend to expand the formal framework

that he inherited from Haydn and Mozart. The Piano Sonata in C major

op. 53 (Waldstein) and the Piano Sonata in F minor op. 57 (Appassionata),

completed in 1804 and 1805 respectively, each employ bold contrasts

in harmony, and they use a broadened formal plan, in which the meditative

slow movements flow directly into the final movements. The symbolism

of the keys used for these sonatas shares in the expressive world

of Beethoven's opera, entitled Leonore in its original version from

1805. The grim F-minor character of the Appassionata recalls the dungeon

scenes in this key from the opera, whereas the jubilant close of the

Waldstein in C major recalls the stirring C-major conclusion of the

opera to the words "Hail to the day! Hail to the hour!" The celebrated

Symphony No. 5 in C minor op. 67 from 1808 is the most thematically

concentrated of Beethoven's works. Variants of the four-note motif

that begins this symphony drive all four movements. The dramatic turning

point in the symphony�where a sense of foreboding, struggle, or mystery

yields to a triumphant breakthrough�comes at the transition to the

final movement, where the music is reinforced by the entrance of the

trombones. Beethoven uses here a large-scale polarity between the

darker sound of C minor and the brighter, more radiant effect of C

major, which is held largely in reserve until the finale. The series

of gigantic masterpieces of Beethoven's third period include the technically

demanding Hammerklavier Sonata, completed in 1818, about which he

correctly predicted on account of its challenges that "it will be

played fifty years hence," and the Diabelli Variations. The latter

work for piano transforms a trivial waltz by Viennese publisher Anton

Diabelli into an astonishing, seemingly endless series of pieces,

each with a unique character; some are humorous or even parodies.

These and other late works incorporate fugues�melodies played in succession

and interwoven�that reflect Beethoven's lifelong interest in the music

of J. S. Bach (known for his keyboard work Art of the Fugue). Beethoven's

second mass, the Missa Solemnis in D major op. 123 (1823), also poses

formidable technical challenges, as do his fascinating and sometimes

enigmatic last quartets and the Ninth Symphony, whose most readily

accessible movement is the choral finale. IV. Evaluation Print section

Beethoven combined the dramatic classical style of lively contrasts

and symmetrical forms, which was brought to its highest development

by Mozart, with the older tradition of unified musical character that

he found in the music of J. S. Bach. In some early works and especially

in his middle or heroic period, Beethoven gave voice through his music

to the new current of subjectivity and individualism that emerged

in the wake of the French Revolution (1789-1799) and the rise of middle

classes. Beethoven disdained injustice and tyranny, and used his art

to sing the praises of the Enlightenment, an 18th-century movement

that promoted the ideals of freedom and equality, even as hopes faded

for progress through political change. (His angry cancellation of

the dedication of the Eroica Symphony to Napoleon Bonaparte reveals

Beethoven's refusal to compromise his principles.) The fact that Beethoven

realized his artistic ambitions in spite of his hearing impairment

added to the fascination and inspiration of his life for posterity,

and the extraordinary richness and complexity of his later works insured

that no later generation would fail to find challenge in his music.

Beethoven's artistic achievement cast a long shadow over the 19th

century and beyond, having set a standard against which later composers

would measure their work. Subsequent composers have had to respond

to the challenge of Beethoven's Ninth, which appeared to have taken

the symphony to its ultimate development. Beethoven,

Ludwig van (1770-1827), German composer, considered one of the greatest

musicians of all time. Having begun his career as an outstanding improviser

at the piano and composer of piano music, Beethoven went on to compose

string quartets and other kinds of chamber music, songs, two masses,

an opera, and nine symphonies. His Symphony No. 9 in D minor op. 125

(Choral, completed 1824), perhaps the most famous work of classical

music in existence, culminates in a choral finale based on the poem

"Ode to Joy" by German writer Friedrich von Schiller. Like his opera

Fidelio, op. 72 (1805; revised 1806, 1814) and many other works, the

Ninth Symphony depicts an initial struggle with adversity and concludes

with an uplifting vision of freedom and social harmony. II. Life Print

section Beethoven was born in Bonn. His father's harsh discipline

and alcoholism made his childhood and adolescence difficult. At the

age of 18, after his mother's death, Beethoven placed himself at the

head of the family, taking responsibility for his two younger brothers,

both of whom followed him when he later moved to Vienna, Austria.

In Bonn, Beethoven's most important composition teacher was German

composer Christian Gottlob Neefe, with whom he studied during the

1780s. Neefe used the music of German composer Johann Sebastian Bach

as a cornerstone of instruction, and he later encouraged his student

to study with Austrian composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, whom Beethoven

met briefly in Vienna in 1787. In 1792 Beethoven made another journey

to Vienna to study with Austrian composer Joseph Haydn, and he stayed

there the rest of his life. The combination of forceful, dramatic

power with dreamy introspection in Beethoven's music made a strong

impression in Viennese aristocratic circles and helped win him generous

patrons. Yet just as his success seemed assured, he was confronted

with the loss of that sense on which he so depended, his hearing.

Beethoven expressed his despair over his increasing hearing loss in

his moving "Heiligenstadt Testament," a document written to his brothers

in 1802. This impairment gradually put an end to his performing career.

However, Beethoven's compositional achievements did not suffer from

his hearing loss but instead gained in richness and power over the

years. His artistic growth was reflected in a series of masterpieces,

including the Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major op. 55 (the Eroica, completed

1804), Fidelio, and the Symphony No. 5 in C minor op. 67 (1808). These

works embody his second period, which is called his heroic style.

Around 1810 Beethoven was especially drawn to the poetry and drama

of German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, whom he met in 1812 through

the initiative of Goethe's young literary friend Bettina Brentano.

Bettina's sister-in-law Antonia Brentano was probably the intended

recipient of Beethoven's famous letter to the "Immortal Beloved."

The letter dates from July 1812 and apparently marks the collapse

of Beethoven's hopes to seek happiness through marriage. Following

this disappointment, Beethoven's output declined significantly, and

during 1813 he was generally depressed and unproductive. Beethoven's

fame during his lifetime reached its peak in 1814. The enthusiastic

response of the public to his music at this time was focused on showy

works, such as Wellington's Victory op. 91 (1813; also known as the

Battle Symphony), and a series of patriotic crowd-pleasers, including

the cantata The Glorious Moment op. 136 (1814), but his enhanced popularity

also made possible the successful revival of Fidelio. During the last

decade of his life Beethoven had almost completely lost his hearing,

and he was increasingly socially isolated. He had assumed the guardianship

of his nephew Karl after a lengthy legal struggle, and despite Beethoven's

affection for Karl, there was enormous friction between the two. Notwithstanding

these difficulties, between 1818 and 1826 Beethoven embarked upon

a series of ambitious large-scale compositions, including the Sonata

in B-flat major op. 106 (Hammerklavier, 1818), the Missa Solemnis

in D major op. 123 (1823), the Thirty-Three Variations on a Waltz

by Diabelli in C major op. 120 (1823), the Symphony No. 9 in D minor

op. 125 (1824), and his last string quartets. Plagued at times by

serious illness, Beethoven nevertheless maintained his sense of humor

and often amused himself with jokes and puns. He continued to work

at a high level of creativity until he contracted pneumonia in December

1826. He died in Vienna in March 1827. III. Music Print section Beethoven's

music is generally divided into three main creative periods. The first,

or early, period extends to about 1802, when the composer made reference

to a "new manner" or "new way" in connection with his art. The second,

or middle, period extends to about 1812, after the completion of his

Seventh and Eighth symphonies. The third, or late, period emerged

gradually; Beethoven composed its pivotal work, the Hammerklavier

Sonata, in 1818. Beethoven's late style is especially innovative,

and his last five quartets, written between 1824 and 1826, can be

regarded as marking the onset of a fourth creative period. Although

Beethoven's music of the early period is sometimes described as imitative

of Mozart and Haydn, much of it is startlingly original, especially

the works for piano. His early piano sonatas often have a forceful,

bold quality, which is set into relief by the searching inwardness

of the slow movements. The Sonata in C minor op. 13 (Path�tique, 1798),

the most famous of these sonatas, transfers Haydn's practice of employing

slow introductions to his symphonies to the genre of the sonata. The

title refers to a quality of pathos or suffering, which is felt especially

in the brooding slow introduction and is twice recalled in later stages

of the first movement. The main body of this swift, brilliant movement

seems to convey willful resistance to the sense of suffering that

dominates the slow introduction. At the threshold of his middle period

Beethoven sought a variety of new approaches to musical form. In the

Sonata in C-sharp minor (Moonlight, 1801), he begins with a slow movement,

while typical sonatas of that time began with a fast movement. The

movement's placid motif (repeated phrase) of broken chords is reinterpreted

in the final movement as forceful figuration reaching across the entire

keyboard. The sonatas of op. 31, from 1802, each open in an original

fashion. The G major, op. 31 no. 1, begins with striking shifts in

key, in contrast to the usual practice of remaining in the same key

to "ground" the listener. The D minor, op. 31 no. 2 (Tempest), on

the other hand, breaks up the opening theme into contrasting segments

in different tempi, whereas customary practice called for stating

the theme in its entirety at the beginning of a movement. In the first

movement of the Eroica Symphony, one of the major works from Beethoven's

middle period, he again sought ways to expand upon the prevailing

musical forms. At that time, composers usually organized movements

in three major parts. First, the exposition introduces the musical

themes of the piece. Next, the development takes these themes into

other keys, often modifying or fragmenting them. Finally, the recapitulation

restates the themes, grounded in the original key. Prefaced by two

massive, emphatic chords, the opening theme of the Eroica lingers

on a mysterious dark moment of harmony�a gesture that is not reinterpreted

until much later, at the outset of the recapitulation. After the rhythmic

climax of the enormous development section�it is twice as long as

the development section in any other symphony of the time�Beethoven

reshapes classical norms by introducing extensive new material, which

is resolved in a sort of recapitulation in the coda (concluding passage),

which follows the movement's recapitulation. The four movements of

the Eroica bear the following expressive associations: struggle, death

(a funeral march), rebirth (a scherzo, or rapid dancelike movement,

that begins quietly), and glorification. In its narrative design,

the Eroica is connected to the ballet music of Beethoven's Prometheus,

op. 43 (1801), from which he borrowed the theme for the symphony's

finale. This movement of the symphony expresses the exaltation of

the Greek mythological figure Prometheus in a series of variations

on the ballet's theme. Beethoven had originally intended to dedicate

the work to French general Napoleon Bonaparte, whom he idolized, but

he angrily withdrew the dedication after learning that Napoleon had

taken the title of emperor. Beethoven's other instrumental works from

the period of the Eroica also tend to expand the formal framework

that he inherited from Haydn and Mozart. The Piano Sonata in C major

op. 53 (Waldstein) and the Piano Sonata in F minor op. 57 (Appassionata),

completed in 1804 and 1805 respectively, each employ bold contrasts

in harmony, and they use a broadened formal plan, in which the meditative

slow movements flow directly into the final movements. The symbolism

of the keys used for these sonatas shares in the expressive world

of Beethoven's opera, entitled Leonore in its original version from

1805. The grim F-minor character of the Appassionata recalls the dungeon

scenes in this key from the opera, whereas the jubilant close of the

Waldstein in C major recalls the stirring C-major conclusion of the

opera to the words "Hail to the day! Hail to the hour!" The celebrated

Symphony No. 5 in C minor op. 67 from 1808 is the most thematically

concentrated of Beethoven's works. Variants of the four-note motif

that begins this symphony drive all four movements. The dramatic turning

point in the symphony�where a sense of foreboding, struggle, or mystery

yields to a triumphant breakthrough�comes at the transition to the

final movement, where the music is reinforced by the entrance of the

trombones. Beethoven uses here a large-scale polarity between the

darker sound of C minor and the brighter, more radiant effect of C

major, which is held largely in reserve until the finale. The series

of gigantic masterpieces of Beethoven's third period include the technically

demanding Hammerklavier Sonata, completed in 1818, about which he

correctly predicted on account of its challenges that "it will be

played fifty years hence," and the Diabelli Variations. The latter

work for piano transforms a trivial waltz by Viennese publisher Anton

Diabelli into an astonishing, seemingly endless series of pieces,

each with a unique character; some are humorous or even parodies.

These and other late works incorporate fugues�melodies played in succession

and interwoven�that reflect Beethoven's lifelong interest in the music

of J. S. Bach (known for his keyboard work Art of the Fugue). Beethoven's

second mass, the Missa Solemnis in D major op. 123 (1823), also poses

formidable technical challenges, as do his fascinating and sometimes

enigmatic last quartets and the Ninth Symphony, whose most readily

accessible movement is the choral finale. IV. Evaluation Print section

Beethoven combined the dramatic classical style of lively contrasts

and symmetrical forms, which was brought to its highest development

by Mozart, with the older tradition of unified musical character that

he found in the music of J. S. Bach. In some early works and especially

in his middle or heroic period, Beethoven gave voice through his music

to the new current of subjectivity and individualism that emerged

in the wake of the French Revolution (1789-1799) and the rise of middle

classes. Beethoven disdained injustice and tyranny, and used his art

to sing the praises of the Enlightenment, an 18th-century movement

that promoted the ideals of freedom and equality, even as hopes faded

for progress through political change. (His angry cancellation of

the dedication of the Eroica Symphony to Napoleon Bonaparte reveals

Beethoven's refusal to compromise his principles.) The fact that Beethoven

realized his artistic ambitions in spite of his hearing impairment

added to the fascination and inspiration of his life for posterity,

and the extraordinary richness and complexity of his later works insured

that no later generation would fail to find challenge in his music.

Beethoven's artistic achievement cast a long shadow over the 19th

century and beyond, having set a standard against which later composers

would measure their work. Subsequent composers have had to respond

to the challenge of Beethoven's Ninth, which appeared to have taken

the symphony to its ultimate development.

|